Vulture African Child Suicide Photographer

The Ultimate in Unfair

War doesn't determine who is right, war determines who is left.

– Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), English philosopher, author, 1950 Nobel Prize-winner in Literature

This photograph showing a starving Sudanese child being stalked by a vulture won Kevin Carter the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography.

Photographer Haunted by Horror of His Work

Obituary: Kevin Carter 1960 - 1994

Johannesburg - Kevin Carter, the South African photographer whose image of a starving Sudanese toddler stalked by a vulture won him a Pulitzer Prize this year, was found dead on Wednesday night, apparently a suicide, police said yesterday. He was 33. The police said Mr Carter's body and several letters to friends and family were discovered in his pick-up truck, parked in a Johannesburg suburb. An inquest showed that he had died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Johannesburg - Kevin Carter, the South African photographer whose image of a starving Sudanese toddler stalked by a vulture won him a Pulitzer Prize this year, was found dead on Wednesday night, apparently a suicide, police said yesterday. He was 33. The police said Mr Carter's body and several letters to friends and family were discovered in his pick-up truck, parked in a Johannesburg suburb. An inquest showed that he had died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Mr Carter started as a sports photographer in 1983 but soon moved to the front lines of South African political strife, recording images of repression, anti-apartheid protest and fratricidal violence. A few davs after winning his Pulitzer Prize in April, Mr Carter was nearby when one of his closest friends and professional companions, Ken Oosterbroek, was shot dead photographing a gun battle in Tokoza township.

Friends said Mr Carter was a man of tumultuous emotions which brought passion to his work but also drove him to extremes of elation and depression. Last year, saying he needed a break from South Africa's turmoil, he paid his own way to the southern Sudan to photograph a civil war and famine that he felt the world was overlooking.

His picture of an emaciated girl collapsing on the way to a feeding centre, as a plump vulture lurked in the background, was published first in The New York Times and The Mail & Guardian, a Johannesburg weekly. The reaction to the picture was so strong that The New York Times published an unusual editor's note on the fate of the girl. Mr Carter said she resumed her trek to the feeding centre. He chased away the vulture.

Afterwards, he told an interviewer, he sat under a tree for a long time, "smoking cigarettes and crying". His father, Mr Jimmy Carter laid last night: "Kevin always carried around the horror of the work he did." - The New York Times

Source: Sydney Morning Herald Saturday 30 July 1994

![]()

What are the odds the little girl is alive today? Not very high, I'd say. If she is alive, what quality of life is she likely to have? She almost certainly has permanent damage from her period of starvation during crucial development, both before and after birth. It is easy to criticise Kevin Carter. Why? Because he took a photo of one starving child among thousands? Let those who send all their spare cash to the needy cast the first stone...

![]()

The Life and Death of Kevin Carter

by Scott MacLeod

As Time's Johannesburg bureau chief for the past five years, Scott MacLeod has seen more than his share of tragedy. But nothing prepared him for the devastating news in July that a colleague, 33-year-old South African photojournalist Kevin Carter, had killed himself. Carter was famous in South Africa for his fearless coverage of deadly township violence, and he had become internationally known for his Pulitzer prizewinning photo of a vulture coolly eyeing an emaciated Sudanese child struggling toward a feeding station. "Few journalists saw as much violence and trauma as he did," says MacLeod. Shocked by Carter's suicide, MacLeod determined "to understand as best I could the complexities behind his tragic end."

The result is this week's unusual tale of a troubled man's life and death. In any given issue of Time, we include, of course, many stories that are driven by news headlines. Occasionally we go back to a seemingly small event of months ago, briefly noted at the time, that strikes us as ripe with human drama and moral implications, worthy of detailed digging and sober reflection. The suicide of Kevin Carter was such an event. In researching the article, MacLeod interviewed Carter's family, close friends and colleagues, as well as experts on suicide; in the process he encountered several other journalists in pursuit of the mystery of Carter's self-destruction. But the subject eluded easy conclusions and assumptions.

MacLeod sees Carter's story as representative of a darker side of middle-class white South Africa and as a warning about the lingering effects of apartheid on all of that country's people. "The lives of some whites too were disrupted and even destroyed by the social experiment," he notes. "I wanted to show that side of the apartheid story as well."

Elizabeth Valk Long

President, Time Domestic

Johannesburg - Visiting Sudan, a little-known photographer took a picture that made the world weep. What happened afterward is a tragedy of another sort. The image presaged no celebration: a child barely alive, a vulture so eager for carrion. Yet the photograph that epitomised Sudan's famine would win Kevin Carter fame - and hopes for anchoring a career spent hounding the news, free-lancing in war zones, waiting anxiously for assignments amid dire finances, staying in the line of fire for that one great picture. On May 23, 14 months after capturing that memorable scene, Carter walked up to the dais in the classical rotunda of Columbia University's Low Memorial Library and received the Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. The South African soaked up the attention. "I swear I got the most applause of anybody," Carter wrote back to his parents in Johannesburg. "I can't wait to show you the trophy. It is the most precious thing, and the highest acknowledgment of my work I could receive."

Carter was feted at some of the most fashionable spots in New York City. Restaurant patrons, overhearing his claim to fame, would come up and ask for his autograph. Photo editors at the major magazines wanted to meet the new hotshot, dressed in his black jeans and T shirts, with the tribal bracelets and diamond-stud earring, with the war-weary eyes and tales from the front lines of Nelson Mandela's new South Africa. Carter signed with Sygma, a prestigious picture agency representing 200 of the world's best photojournalists. "It can be a very glamorous business," says Sygma's US director, Eliane Laffont. "It's very hard to make it, but Kevin is one of the few who really broke through. The pretty girls were falling for him, and everybody wanted to hear what he had to say."

There would be little time for that. Two months after receiving his Pulitzer, Carter would be dead of carbon-monoxide poisoning in Johannesburg, a suicide at 33. His red pickup truck was parked near a small river where he used to play as a child; a green garden hose attached to the vehicle's exhaust funneled the fumes inside. "I'm really, really sorry," he explained in a note left on the passenger seat beneath a knapsack. "The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist."

How could a man who had moved so many people with his work end up a suicide so soon after his great triumph? The brief obituaries that appeared around the world suggested a morality tale about a person undone by the curse of fame. The details, however, show how fame was only the final, dramatic sting of a death foretold by Carter's personality, the pressure to be first where the action is, the fear that his pictures were never good enough, the existential lucidity that came to him from surviving violence again and again - and the drugs he used to banish that lucidity. If there is a paramount lesson to be drawn from Carter's meteoric rise and fall, it is that tragedy does not always have heroic dimensions. "I have always had it all at my feet," read the last words of his suicide note, "but being me just fit up anyway."

First, there was history. Kevin Carter was born in 1960, the year Nelson Mandela's African National Congress was outlawed. Descended from English immigrants, Carter was not part of the Afrikaner mainstream that ruled the country. Indeed, its ideology appalled him. Yet he was caught up in its historic misadventure. His devoutly Roman Catholic parents, Jimmy and Roma, lived in Parkmore, a tree-lined Johannesburg suburb - and they accepted apartheid. Kevin, however, like many of his generation, soon began to question it openly. "The police used to go around arresting black people for not carrying their passes," his mother recalls. "They used to treat them very badly, and we felt unable to do anything about it. But Kevin got very angry about it. He used to have arguments with his father. "Why couldn't we do something about it? Why didn't we go shout at those police?"

Though Carter insisted he loved his parents, he told his closest friends his childhood was unhappy. As a teenager, he found his thrills riding motorcycles and fantasized about becoming a race-car driver. After graduating from a Catholic boarding school in Pretoria in 1976, Carter studied pharmacy before dropping out with bad grades a year later. Without a student deferment, he was conscripted into the South African Defense Force (SADF), where he found upholding the apartheid regime loathsome. Once, after he took the side of a black mess-hall waiter, some Afrikaans-speaking soldiers called him a kaffir-boetie ("nigger lover") and beat him up. In 1980 Carter went absent without leave, rode a motorcycle to Durban and, calling himself David, became a disk jockey. He longed to see his family but felt too ashamed to return. One day after he lost his job, he swallowed scores of sleeping pills, pain-killers and rat poison. He survived. He returned to the SADF to finish his service and was injured in 1983 while on guard duty at air force headquarters in Pretoria. A bomb attributed to the ANC had exploded, killing 19 people. After leaving the service, Carter got a job at a camera supply shop and drifted into journalism, first as a weekend sports photographer for the Johannesburg Sunday Express. When riots began sweeping the black townships in 1984, Carter moved to the Johannesburg Star and aligned himself with the crop of young, white photojournalists who wanted to expose the brutality of apartheid - a mission that had once been the almost exclusive calling of South Africa's black photographers. "They put themselves in face of danger, were arrested numerous times, but never quit. They literally were willing to sacrifice themselves for what they believed in," says American photojournalist James Nachtwey, who frequently worked with Carter and his friends. By 1990, civil war was raging between Mandela's ANC and the Zulu-supported Inkatha Freedom Party. For whites, it became potentially fatal to work the townships alone. To diminish the dangers, Carter hooked up with three friends - Ken Oosterbroek of the Star and free-lancers Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva - and they began moving through Soweto and Tokoza at dawn. If a murderous gang was going to shoot up a bus, throw someone off a train or cut up somebody on the street, it was most likely to happen as township dwellers began their journeys to work in the soft, shadowy light of an African morning. The four became so well known for capturing the violence that Living, a Johannesburg magazine, dubbed them "the Bang-Bang Club."

Even with the teamwork, however, cruising the townships was often a perilous affair. Well-armed government security forces used excessive firepower. The chaotic hand-to-hand street fighting between black factions involved AK-47s, spears and axes. "At a funeral some mourners caught one guy, hacked him, shot him, ran over him with a car and set him on fire," says Silva, describing a typical encounter. "My first photo showed this guy on the ground as the crowd told him they were going to kill him. We were lucky to get away."

Sometimes it took more than a camera and camaraderie to get through the work. Marijuana, known locally as dagga, is widely available in South Africa. Carter and many other photojournalists smoked it habitually in the townships, partly to relieve tension and partly to bond with gun-toting street warriors. Although he denied it, Carter, like many hard-core dagga users, moved on to something more dangerous: smoking the "white pipe," a mixture of dagga and Mandrax, a banned tranquiliser containing methaqualone. It provides an intense, immediate kick and then allows the user to mellow out for an hour or two.

By 1991, working on the dawn patrol had paid off for one of the Bang-Bang Club. Marinovich won a Pulitzer for his September 1990 photographs of a Zulu being stabbed to death by ANC supporters. That prize raised the stakes for the rest of the club - especially Carter. And for Carter other comparisons cropped up. Though Oosterbroek was his best friend, they were, according to Nachtwey, "like the polarities of personality types. Ken was the successful photographer with the loving wife. His life was in order." Carter had bounced from romance to romance, fathering a daughter out of wedlock. In 1993 Carter headed north of the border with Silva to photograph the rebel movement in famine-stricken Sudan. To make the trip, Carter had taken a leave from the Weekly Mail and borrowed money for the air fare. Immediately after their plane touched down in the village of Ayod, Carter began snapping photos of famine victims. Seeking relief from the sight of masses of people starving to death, he wandered into the open bush. He heard a soft, high-pitched whimpering and saw a tiny girl trying to make her way to the feeding centre. As he crouched to photograph her, a vulture landed in view. Careful not to disturb the bird, he positioned himself for the best possible image. He would later say he waited about 20 minutes, hoping the vulture would spread its wings. It did not, and after he took his photographs, he chased the bird away and watched as the little girl resumed her struggle. Afterward he sat under a tree, lit a cigarette, talked to God and cried. "He was depressed afterward," Silva recalls. "He kept saying he wanted to hug his daughter."

After another day in Sudan, Carter returned to Johannesburg. Coincidentally, the New York Times, which was looking for pictures of Sudan, bought his photograph and ran it on 26 March 1993. The picture immediately became an icon of Africa's anguish. Hundreds of people wrote and called the Times asking what had happened to the child (the paper reported that it was not known whether she reached the feeding centre); and papers around the world reproduced the photo. Friends and colleagues complimented Carter on his feat. His self-confidence climbed.

Carter quit the Weekly Mail and became a free-lance photojournalist - an alluring but financially risky way of making a living, providing no job security, no health insurance and no death benefits. He eventually signed up with the Reuter news agency for a guarantee of roughly $2,000 a month and began to lay plans for covering his country's first multiracial elections in April. The next few weeks, however, would bring depression and self-doubt, only momentarily interrupted by triumph. The troubles started on 11 March. Carter was covering the unsuccessful invasion of Bophuthatswana by white right-wing vigilantes intent on propping up a black homeland, a showcase of apartheid. Carter found himself just feet away from the summary execution of right-wingers by a black "Bop" policeman. "Lying in the middle of the gunfight," he said, "I was wondering about which millisecond next I was going to die, about putting something on film they could use as my last picture."

His pictures would eventually be splashed across front pages around the world, but he came away from the scene in a funk. First, there was the horror of having witnessed murder. Perhaps as importantly, while a few colleagues had framed the scene perfectly, Carter was reloading his camera with film just as the executions took place. "I knew I had missed this f--- shot," he said subsequently. "I drank a bottle of bourbon that night."

At the same time, he seemed to be stepping up his drug habit, including smoking the white pipe. A week after the Bop executions, he was seen staggering around while on assignment at a Mandela rally in Johannesburg. Later he crashed his car into a suburban house and was thrown in jail for 10 hours on suspicion of drunken driving. His superior at Reuter was furious at having to go to the police station to recover Carter's film of the Mandela event. Carter's girlfriend, Kathy Davidson, a schoolteacher, was even more upset. Drugs had become a growing issue in their one-year relationship. Over Easter, she asked Carter to move out until he cleaned up his life.

With only weeks to go before the elections, Carter's job at Reuter was shaky, his love life was in jeopardy and he was scrambling to find a new place to live. And then, on 12 April 1994, the New York Times phoned to tell him he had won the Pulitzer. As jubilant Times foreign picture editor Nancy Buirski gave him the news, Carter found himself rambling on about his personal problems. "Kevin!" she interrupted, "You've just won a Pulitzer! These things aren't going to be that important now."

Early on Monday 18 April, the Bang-Bang Club headed out to Tokoza township, 10 miles from downtown Johannesburg, to cover an outbreak of violence. Shortly before noon, with the sun too bright for taking good pictures, Carter returned to the city. Then on the radio he heard that his best friend, Oosterbroek, had been killed in Tokoza. Marinovich had been gravely wounded. Oosterbroek's death devastated Carter, and he returned to work in Tokoza the next day, even though the violence had escalated. He later told friends that he and not Ken "should have taken the bullet."

New York was a respite. By all accounts, Carter made the most of his first visit to Manhattan. The Times flew him in and put him up at the Marriott Marquis just off Times Square. His spirits soaring, he took to calling New York "my town." With the Pulitzer, however, he had to deal not only with acclaim but also with the critical focus that comes with fame. Some journalists in South Africa called his prize a "fluke," alleging that he had somehow set up the tableau. Others questioned his ethics. "The man adjusting his lens to take just the right frame of her suffering," said theSt Petersburg (Florida) Times, "might just as well be a predator, another vulture on the scene." Even some of Carter's friends wondered aloud why he had not helped the girl.

Carter was painfully aware of the photojournalist's dilemma. "I had to think visually," he said once, describing a shoot-out. "I am zooming in on a tight shot of the dead guy and a splash of red. Going into his khaki uniform in a pool of blood in the sand. The dead man's face is slightly gray. You are making a visual here. But inside something is screaming, 'My God.' But it is time to work. Deal with the rest later. If you can't do it, get out of the game." Says Nachtwey, "Every photographer who has been involved in these stories has been affected. You become changed forever. Nobody does this kind of work to make themselves feel good. It is very hard to continue."

Carter did not look forward to going home. Summer was just beginning in New York, but late June was still winter in South Africa, and Carter became depressed almost as soon as he got off the plane. "Jo'burg is dry and brown and cold and dead, and so damn full of bad memories and absent friends," he wrote in a letter never mailed to a friend, Esquire picture editor Marianne Butler in New York.

Nevertheless, Carter carefully listed story ideas and faxed some of them off to Sygma. Work did not proceed smoothly. Though it was not his fault, Carter felt guilty when a bureaucratic foul-up caused the cancellation of an interview by a writer from Parade magazine, a Sygma client, with Mandela in Cape Town. Then came an even more unpleasant experience. Sygma told Carter to stay in Cape Town and cover French President Francois Mitterrand's state visit to South Africa. The story was spot news, but according to editors at Sygma's Paris office, Carter shipped his film too late to be of use. In any case, they complained, the quality of the photos was too poor to offer to Sygma's clients.

According to friends, Carter began talking openly about suicide. Part of his anxiety was over the Mitterrand assignment. But mostly he seemed worried about money and making ends meet. When an assignment in Mozambique for Time came his way, he eagerly accepted. Despite setting three alarm clocks to make his early-morning flight on July 20, he missed the plane. Furthermore, after six days in Mozambique, he walked off his return flight to Johannesburg, leaving a package of undeveloped film on his seat. He realised his mistake when he arrived at a friend's house. He raced back to the airport but failed to turn up anything. Carter was distraught and returned to the friend's house in the morning, threatening to smoke a white pipe and gas himself to death.

Carter and a friend, Judith Matloff, 36, an American correspondent for Reuter, dined on Mozambican prawns he had brought back. He was apparently too ashamed to tell her about the lost film. Instead they discussed their futures. Carter proposed forming a writer-photographer free-lance team and traveling Africa together.

On the morning of Wednesday 27July, the last day of his life, Carter appeared cheerful. He remained in bed until nearly noon and then went to drop off a picture that had been requested by the Weekly Mail. In the paper's newsroom, he poured out his anguish to former colleagues, one of whom gave him the number of a therapist and urged him to phone her. The last person to see Carter alive, it seems, was Oosterbroek's widow, Monica. As night fell, Carter turned up unannounced at her home to vent his troubles. Still recovering from her husband's death 3 months earlier, she was in little condition to offer counsel. They parted at about 5:30pm.

The Braamfonteinspruit is a small river that cuts southward through Johannesburg's northern suburbs - and through Parkmore, where the Carters once lived. At around 9pm, Kevin Carter backed his red Nissan pickup truck against a blue gum tree at the Field and Study Centre. He had played there often as a little boy. The Sandton Bird Club was having its monthly meeting there, but nobody saw Carter as he used silver gaffer tape to attach a garden hose to the exhaust pipe and run it to the passenger-side window. Wearing unwashed Lee jeans and an Esquire T shirt, he got in and switched on the engine. Then he put music on his Walkman and lay over on his side, using the knapsack as a pillow.

The suicide note he left behind is a litany of nightmares and dark visions, a clutching attempt at autobiography, self-analysis, explanation, excuse. After coming home from New York, he wrote, he was "depressed ... without phone ... money for rent ... money for child support ... money for debts ... money!!! ... I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain ... of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners..." And then this: "I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky."

Source: Time magazine 12 September 1994 Volume 144 Number 11

from Time Domestic

3 October 1994 Volume 144 Number 14

Letters:

Suicide of a Pulitzer Winner

It is tragic that the world has lost a photographer with the talent and skill of Kevin Carter. But it should come as no surprise that he found it difficult to reconcile the peaks and valleys of his career with the suffering and violence upon which it was built. It disturbed him, as it should have. By embarking on a career in photojournalism, Carter set himself apart from the lives of the people he photographed. He chose to be an observer rather than a participant. Carter opted for a moral detachment that most of us cannot achieve and that I would not want to have. Though I can admire his work and courage in the face of danger, I cannot imagine witnessing such violence and human suffering without trying to intervene. Perhaps, in the end, Kevin Carter could not either.

Andrew W Hall

Galveston, Texas AOL: Tigone

![]()

As Kevin Carter's sister, I am sad that Time has stooped to such sensationalist reporting concerning my brother's death. Scott MacLeod did not interview me or my sister or two of Kevin's very close friends. His "detailed digging" resulted in the presentation of a series of negative issues through which he attempted to explain a suicide. Suicide is obviously the result of the negative outweighing the positive, in the victim's mind, but this does not mean that there were not hundreds of positive aspects to the particular individual. Kevin was a person of passion and presence; he left his mark wherever he went. He was an incredible father to Megan and a man who grappled deeply with issues most people just accept. In many ways he was ahead of his time. The pain of his mission to open the eyes of the world to so many of the issues and injustices that tore at his own soul eventually got to him. The year 1993 was a good one for him, but at the end of it he told me he really needed a break from Africa, that it was getting to him. He knew then that he was losing perspective. Unfortunately, the pressure only got worse, with the increased violence leading up to the elections and, worst of all, the loss of his friend Ken Oosterbroek. The Pulitzer Prize certainly didn't send Kevin "deeper into anguish." If anything, it was a confirmation that his work had all been worthwhile. Your version of Kevin's death seems so futile. What is anyone going to learn or gain from reading it?

Patricia Gird Randburg

South Africa

![]()

-It is ironic that Kevin Carter won the Pulitzer for a photograph which to me is a photograph of his own soul and epitomizes his life. Kevin is that small child huddled against the world, and the vulture is the angel of death. I wish someone could have chased that evil from his life. I'm sure that little child succumbed to death just as Kevin did. Both must have suffered greatly.

Joanne Cauciella Bonica

Massapequa, New York

Source: home-4.tiscali.nl

![]()

-------- Original Message --------

Subject: Other

Date: 10 Aug 2005 04:27:50 -0000

This message was posted via the Feedback form.

Comments: Kevin Carter took that picture of that little Sudanese girl and walked on to under a tree to calmly have a cigarette. Shit, I would have stomped that bird, picked up that baby, put her in my camera bag and gotten her to a hospital and then adopted her. But her little bones are laying in the Sundan sun bleached white by now.

That photo is why I believe that man keeps deluding himself in believing in a "God". There is no God. If there is and it could allow that to happen to such a sweet little innocent being it's a perverse and sick "God". The photo outrages me. We keep spending money on weapons, we keep electing men to power that are weak and feeble minded, we let millions of beings both human and animals suffer horrendously daily and look the other way.

I'm not a "nut" I'm just tired of the cruelty that stems from mankind's stupidity.

Claudia

Claudia,

I think you'll find that it's much easier to criticise than it is to act. Have you adopted an orphan? Joined a political activist group? No? Oh.

I don't accept the idea of God myself, but certainly not for the reason that bad things happen to people and animals.

![]()

The Atrocity Exhibition: A War Fuelled by Imagery

by Charles Paul Freund

In 1993, a photographer named Kevin Carter went to Sudan to capture images of that nation's dismal and unending civil war. One of the pictures he took was of a starving little girl: she had collapsed in the bush, and a vulture nearby seemed to be waiting for her to die. The photo was reproduced all over the world, touching many thousands of people, becoming an icon of African misery, winning a Pulitzer Prize, and, a year later, apparently contributing to Carter's own suicide.

In 1993, a photographer named Kevin Carter went to Sudan to capture images of that nation's dismal and unending civil war. One of the pictures he took was of a starving little girl: she had collapsed in the bush, and a vulture nearby seemed to be waiting for her to die. The photo was reproduced all over the world, touching many thousands of people, becoming an icon of African misery, winning a Pulitzer Prize, and, a year later, apparently contributing to Carter's own suicide.

Carter, a white South African, spent only a couple of days in Sudan. According to Susan D Moeller, who tells Carter's story in Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death, he had gone into the bush seeking relief from the terrible starvation and suffering he was documenting, when he encountered the emaciated girl. When he saw the vulture land, Carter waited quietly, hoping the bird would spread its wings and give him an even more dramatic image. It didn't, and he eventually chased the bird away. The girl gathered her strength and resumed her journey toward a feeding centre. Afterward, writes Moeller, Carter "sat by a tree, talked to God, cried, and thought about his own daughter, Megan."

When the image of the prostrate girl and the patient vulture appeared, many people demanded to know what had happened to her. The New York Times explained in an editors' note that while she resumed her trek, the photographer didn't know if she had survived. Carter stood accused; callers in the middle of the night denounced him. The girl began to haunt the photographer. In June 1994, Carter, beset by difficulties, killed himself. His suicide note speaks of the ghosts he could not escape, the "vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain," and the "starving and wounded children" ever before his eyes.

This death of a messenger is a cautionary tale for an age of atrocity imagery. Terrible pictures of agony and murder have come to America from Lebanon, from Somalia, from Haiti, from Rwanda, and now from Kosovo, and they have unleashed the most powerful of emotions. Yet these emotions emerge from pictures that tell inevitably distorted versions of their awful realities. Their concrete representations suggest a moral imperative to act, to intervene with force against evil. Yet the resulting interventions have, one after the other, revealed the illusions of mercy: there is no such thing as military humanitarianism. Such action, despite its moral incentive, is always political, and always results in political consequences and responsibilities. When these assert themselves, the atrocity imagery changes: it often features Americans.

In Carter's case, Western newspaper readers saw a little girl. Carter, in the Sudanese village where he landed, was watching 20 people starve to death each hour. Perhaps he might have laid aside his camera to give the victims what succor he could (and thus never have encountered the girl in the bush); perhaps his photographs could have led to greater help than he could personally give. Should he have carried one girl to safety? Carter was surrounded by hundreds of starving children. When he sat by the tree and wept, it was beneath a burden of futility. But his was not a photo of futility, nor of mass starvation, nor of religious factionalism, nor of civil war. Readers saw a little girl. In part, at least, Carter died for that.

In Carter's case, Western newspaper readers saw a little girl. Carter, in the Sudanese village where he landed, was watching 20 people starve to death each hour. Perhaps he might have laid aside his camera to give the victims what succor he could (and thus never have encountered the girl in the bush); perhaps his photographs could have led to greater help than he could personally give. Should he have carried one girl to safety? Carter was surrounded by hundreds of starving children. When he sat by the tree and wept, it was beneath a burden of futility. But his was not a photo of futility, nor of mass starvation, nor of religious factionalism, nor of civil war. Readers saw a little girl. In part, at least, Carter died for that.

While Kevin Carter was in Sudan, American forces were not very far away: they were in Somalia. They'd been dispatched there by George Bush, who specifically cited the "shocking images" of starvation and violence from that collapsed nation when he announced a humanitarian intervention. The use of America's military power for such purposes had broad public support; indeed, Bush was actually under pressure to act as a result of the deeply disturbing imagery. The Cold War was over; history had ended with the collapse of ideological challenge to liberal democratic capitalism. America's enormous military power could become an arsenal for decency.

But it turns out that war is fought on history's nether side. The post-historical urge to rescue, as it emerges from dangerously sentimentalised atrocity imagery, is considerably weaker in practice than is the historical urge to power that it confronts on the ground.

American forces, under Bill Clinton, altered their Somali mission from one of alleviating hunger to one of "nation building," thus involving the US military in a local political struggle that policy makers didn't take seriously. The result was that the United States, in all its might, was driven from Somalia by a local militia leader whose followers dragged the despoiled corpses of some American soldiers through the streets. Somalia remains the "failed state" it was before American troops arrived, its people living in the continuing misery that results from total national dysfunction. But what little imagery emerges from Somalia has seemingly lost its moral dimension; for Americans, at least, such imagery now has political content, and is judged politically when it is displayed at all.

This intervention was itself a replay of the American misadventure in Beirut in 1982, when, in the wake of the massacres at the Sabra and Shattila refugee camps, Ronald Reagan sent in the Marines while citing the terrible pictures of suffering. Though seemingly engaged in a humanitarian effort aimed at policing and stabilizing the volatile situation, Americans actually found themselves enmeshed in a complex political struggle for the control of Lebanon. The Marines were of course pulled out the next year after their barracks were bombed, killing 223 soldiers. The perpetrators of the bombing have never been identified; Lebanon today is controlled by Syria.

The NATO intervention under American leadership in Yugoslavia, over the issue of Kosovo, is the apotheosis of this pathos-driven moral imperative reduced immediately to political dross. In a notoriously rambling 23 March speech intended to frame the issues involved in the Kosovo conflict and to garner support for American military involvement there, the president cited a variety of reasons to take military action, and evoked the horrible pictures of Balkan bloodshed that had appeared in the press for years. He told the country that he wanted to create a world "where we don't have to worry about seeing scenes every night for the next 40 years of ethnic cleansing in some part of the world." With likely images of dead Americans no doubt in mind, the president made it clear in advance of the bombing campaign that there were no plans to send in ground troops.

This attempt to sell a military action on humanitarian grounds, yet split the difference between the two kinds of atrocity images, has had serious consequences: a military, political, and humanitarian miscalculation of historic proportions. NATO's air attacks provided cover for Serbian leader Slobodon Milosevic to begin an expulsion of ethnic Albanians from the Serbian province. Hundreds of thousands of persons have been driven into the fragile countries bordering Kosovo, straining their limited resources, threatening their political stability, and submerging the entire conflict in staggering suffering.

Indeed, although the bombing campaign was originally intended to force Milosevic to sign a NATO-brokered treaty involving Kosovo, the scale of the humanitarian emergency - including reports of murders of Kosovar men - recast him as an unofficial war criminal. That threw into doubt the air campaign's moral underpinnings. After all, what kind of moral victory would it be if a such a perpetrator was forced to sign a treaty, but otherwise retained political power?

Politically, the air campaign seemed to unite Serbians behind Milosevic, although most of them had disliked him and had wanted to get rid of him. Many Serbians felt unfairly targeted: hundreds of thousands of them had recently been driven from Croatia, suffering great hardship with little or no attention from the United States or NATO. Indeed, many Serbians argued that during the Tito dictatorship after World War II they had been driven by the thousands from Kosovo, which they consider their sacred homeland, by the ethnic Albanians who then had power over the province.

As a result of the bombing campaign, NATO seems to have traded its relationship with Russia (where nationalists were threatening to radicalize a fragile political situation) for a marriage of sorts with the Kosovo Liberation Army, a group that the United States had until recently called "terrorists" and provocateurs. The KLA's backing is as murky as its agenda, which reportedly calls for the creation of a "Greater Albania" along the lines of the rump state created by fascist Italian occupiers during World War II. That would appear to require the dismantling not only of Yugoslavia but of Macedonia as well. Yet some members of Congress have called for the arming and support of the organisation.

While the bombing campaign became focused increasingly on the refugee problem it had itself seemingly exacerbated, the Clinton administration fell into visible disarray. The White House appeared completely flummoxed, claiming to have foreseen the expulsions, though obviously failing to prepare for them. Meanwhile, persons in the CIA, the Pentagon, and the State Department leaked stories to the press intended to pass the blame for the stunning mess. It was a singularly dismaying performance.

Yet American public support for continued military action - and even for the introduction of ground forces - actually grew. The power of atrocity imagery continued to assert itself.

In fact, attempting to respond to such images is entirely appropriate; if the United States can alleviate suffering with aid, sanctions, or even military action, then it shold debate doing so, determine if it is willing to accept the foreseeable consequences, and act. But misunderstanding and sentimentalising these images is an invitation to disaster. For all their inherent emotional content, they remain ultimately political in nature. They arise from political circumstances, and one cannot "stop" them without accepting the inevitable political consequences of intervention. The United States cannot pretend that it is the Red Cross with a Pentagon, though a succession of presidents have acted as if it were.

In Haiti, American forces have become virtual prisoners of pathos. They were sent there by Clinton in response to pitiable images of Haitian bloodshed and chaos, and in support of a reform president, and they are now reportedly unable to leave their barracks. Haiti has made no discernible progress toward real democratic practice, and its government - made possible by this American act of militarised humanitarianism - stands accused of murdering its enemies. It is unclear what moral purpose is served by the continued presence in the country of US troops. They remain under close confinement, however, to ensure that they do not become yet more targets of Haiti's endemic political violence, and the subject of more atrocity photographs featuring Americans soldiers.

In Rwanda, President Clinton took no action at all to forestall the true genocide that occurred five years ago, although the United States, France, and Belgium were all forewarned that many thousands of persons would soon be hacked to death by their traditional tribal enemies. However, the pictures of piles of bloody corpses that soon emerged from Rwanda were horrifying, and a massive effort was made to care for the many refugees who soon filled camps outside the country. There were many pitiable images to emerge from these camps as well; these pictures seemed to portray the remnants of a targeted people who had somehow escaped slaughter, and who were now reduced to the misery of refugee camp life. Having failed to stop the murders, the West surely had a moral obligation to give succor to the survivors.

But the details that eventually were reported from the camps were very different. Many of the people in the camps were not survivors of the slaughter; they were either perpetrators of the slaughter or members of the tribe that supported it. They had crowded into the camps to escape retribution. What appeared to be a morally necessary act of sanctuary was revealed to be - in large part, at least - aid and comfort to murderers.

And what of Kashmir? Tibet? The Kurds? Indeed, what of Iraq, where the deaths of many thousands of children have been attributed by the United Nations to the sanctions policy imposed by the United States? "Because we cannot do everything everywhere," says Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, "does not mean we should do nothing nowhere." True as far as it goes. But it also means that when we do choose to act, it should be in full appreciation not only of mercy's limits but of its consequences.

Charles Paul Freund is a Reason senior editor

Source: reason.com Reason Magazine June 1999

![]()

Inner Horror Plagues War Photographers

It is not always bullets or bombs that kill war correspondents, but the horror they keep inside.

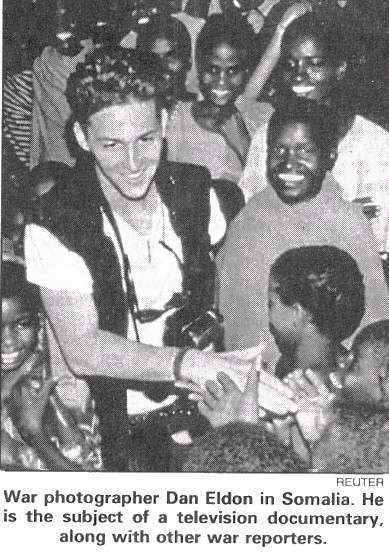

Amy Eldon is too familiar with both causes of death. The young documentary maker lost her older brother, a freelance photographer who worked for Reuters and others, 5 years, ago in Somalia. Now she has learnt that television journalist Carlos Mavroleon, a subject of her new film on battle-zone reporters, died in August of a heroin overdose.

"It is job-related," Eldon said. "So many of these guys, after what they've seen, they become so tormented and they don't know where to put all this horror. Carlos just escaped to another world." Mavroleon was one of several photographers and cameramen Eldon interviewed for her two-hour television documentary Dying to Tell the Story, which premiered on an American cable network.

The film was inspired by her brother Dan, beaten to death in Somalia two months short of his 23rd birthday. After his death, she left college and fought off depression before deciding to make a film about him and other journalists who live to cover wars.

The film was inspired by her brother Dan, beaten to death in Somalia two months short of his 23rd birthday. After his death, she left college and fought off depression before deciding to make a film about him and other journalists who live to cover wars.

"They're cut from a different cloth. They're mad," Eldon said, "I think some go into it and then they become used to a higher threshold of pain. They become adrenaline junkies."

The addiction has left some of Dan's colleagues with a lifetime of pain. Donald McCullin, a self-described "war-a-year" man, now lives in an isolated English manor where cabinets are filled with photos of the dead and dying. Despite quitting, McCullin was haunted by what he had witnessed. A switch to landscape photography was no relief: his photos still look like war zones, Eldon said. "He'll have this beautiful picture of a sparrow that will be dead on white snow and it looks exactly like his pictures from Vietnam or Cambodia. It's frightening."

But Dan Dot only loved adventure, he saw himself performing a public service. Having grown up in Africa, he was concerned about the famine and civil war killing the people of Somalia. "What really motivated Dan was the fact that he was making a difference," his sister said.

"There he was at 21 and was making the double middle-page spread of Time and Newsweek. He was driven by the fact that he was actually galvanising people into action." Once Eldon believed her older brother was invincible. Dubbed by colleagues the Mayor of Mogadishu, Somalia's capital, Dan seemed to know everyone and fear nothing.

But Eldon saw her brother grow increasing tense after his stints in the war-ravaged country. "I was concerned because when you're in a war zone you're so aware of the fragility of life. And you're always on the edge and it's very difficult to sustain that when you go back to normal life. That's why some people get into drugs." Despite Dan's enthusiasm, the conflict wore on him and he said he had "had enough" just before he was killed. He was not addicted to war coverage, she said, and had thoughts of attending film school and making movies.

Dan, whose spirit is "very much around and challenging me to take bigger risks", also left 17 journals of his travels around the world. He filled the pages with photos, drawings and neatly penned writings. Parts of the colourful, complex pages appear in The Journey Is the Destination, published in 1997. The actual notebooks are carefully preserved by Amy and her family. "My mother calls them her grandchildren," Eldon said.

In her documentary, she questions veteran correspondents about why they keep returning to combat zones despite the grimness. Seven journalists were interviewed extensively, including long-time BBC foreign correspondent Martin Bell and CNN's chief international correspondent, Christiane Amanpour.

"There are certain people who have to do what they do and it can't be explained," Amanpour said. Bell takes a humble approach: "We can't be heroes because we can get out when we want," he told Eldon.

Asked if she thinks about the moment of her brother's murder, when a mob of enraged Somalis beat him and three other photographers to death, Eldon says no. "His death was a teaspoon of his life. It was such a brief thing. And the rest was just a tremendous life filled with love and joy." - Reuter

Source: The Dominion Thursday 17 September 1998

![]()

Trauma, Torment of War Reporters

by Carlin Romano

Review of the book Journalists Under Fire: The Psychological Hazards of Covering War by Anthony Feinstein, Johns Hopkins University Press.

'What makes a good newspaperman?" New York Herald Tribune city editor Stanley Walker famously asked in 1928. His reply to that rhetorical question became journalistic lore. "The answer is easy," Walker wrote. "He knows everything... His brain is the repository of the accumulated wisdom of the ages... He can go for nights without sleep. He dresses well and talks with charm. He hates lies and meanness and sham... When he dies, a lot of people are sorry, and some remember him for several days."

The New York Times revived that part-heroic, part-sardonic image of the newspaperman Thursday when, without fear (and with just a little favour), it devoted part of its front page and its entire inside obituary section to one of its own: "R W Apple Jr, Times Globe-Trotter Dies at 71." Over more than 40 years as a correspondent and editor, the Times reported, "Johnny" Apple "wrote from more than 100 countries about war and revolution, politics and government, food and drink, and the revenge of living well..." By any standard of the trade, Apple deserved a salute. He fulfilled the popular image of the American foreign correspondent as a stylish, charismatic, invulnerable character who jets in, gets the story, keeps (in Apple's case) his traveling pepper mill by his side, and makes it home undamaged in time for his daughter's wedding.

But there's a far-less-covered side to this trade, and it's the singular feat of Toronto psychiatrist Anthony Feinstein's Journalists Under Fire to turn his own clinician's light on it. Feinstein quotes from the memoir of another former Times foreign correspondent, Chris Hedges, who provides a searing foreword to this book. In War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, Hedges writes of his goodbye to what Feinstein describes as three "harrowing" trips to El Salvador's civil war:

My last act was, in a frenzy of rage and anguish, to leap over the KLM counter in the airport in Costa Rica because of a perceived slight by a hapless airline clerk. I beat him to the floor as his bewildered colleagues locked themselves in the room behind the counter. Blood streamed down his face and mine. I refused to wipe the dried stains off my cheeks on the flight to Madrid, and I carry a scar on my face from where he thrust his pen into my cheek. War's sickness had become my own.

Feinstein studs his study with such examples of war journalists falling to pieces, experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression. Among the symptoms: uncontrolled anger, distressing images and flashbacks, estrangement from others, troubled sleep, hypervigilance (such as hitting the ground when a child pops a balloon).

Veteran ITN cameraman Jon Steele, at the outset of his memoir, War Junkie, drolly recalls his "emotional disintegration" one day at Heathrow's Terminal Four: "Attention, Club World and World Traveller passengers. British Airways is happy to announce the nervous breakdown of Jon Denis Steele at check-in counter twenty."

London Times reporter Anthony Loyd remains haunted by a Chechen woman who brandished the bloody leg of a bombed family member. British photographer Jon Jones still sees a particular child's severed head under a blanket. A witness to Rwanda's genocide lifts a glass of champagne to his lips in London and immediately takes in the "smell of corpses... . That has happened a lot, the sense that the smell was all over you... it would not go away."

According to Feinstein, "nowhere in the countless pages of journals devoted to psychological trauma is there a single piece of research on war journalists." Filling that gap, he's conducted multiple surveys and many interviews. In one of Feinstein's surveys that analyzed 110 male and 30 female war journalists, "29% of the group had met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD over the course of long careers," compared with about 5% of the general public. Feinstein covers plenty of territory: the special torments of mothers and freelancers among war correspondents; the brutal effect of war journalism on relationships with spouses; the so-called adrenaline junkies among foreign hands; the dysfunctional- family backgrounds of many attracted to foreign coverage; the impact on "domestic" reporters covering incidents like 9/11.

What sticks, though, is the flip side to the upbeat R W Apple image of foreign correspondence. "It slowly takes away your smile," says South African photographer João Silva of the work. One veteran sees dead colleagues walking toward him. Another can no longer eat meat. "Do not delude yourself into thinking," the BBC's Allan Little tells others, "that you can swan in and swan out of other people's wars year after year and not be affected..."

Feinstein believes that journalistic organizations should take more responsibility for the mental health of their foreign correspondents and that newspapers do worse in that regard than broadcasters. What's clear is that while some may remember a journalist for just "several days," war journalists never forget what they've seen on our behalf, and they're never quite the same.

Earth's magnetic field:

Earth's magnetic field:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home