The Gleaners and I -- Les glaneurs et la glaneuse

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (the whole film Spanish subtitles)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gcduo8-GjFs

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNPIe9yLjlw part 2 of 8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LuzfTx78ul4

Clips (Spanish subtitles)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SQIdZM8Kjwc

Trailer (english subtitles)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aKgjjEJvMbM

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gleaners

Rotten Tomatoes

Legendary filmmaker Agnes Varda takes digital camcorder in hand and roams about the French countryside in search of "gleaners." An age-old practice, as depicted in Millet's famous painting, performed traditionally by peasant women, gleaners scavenged the remains of a crop after the harvest. Varda finds their modern-day equivalent collecting rejected potatoes outside of Lyon, fallen apples in Provence, and refuse in the markets of Paris. Along the way, she talks to a man sporting yellow rubber boots who has lived on trash for ten years, a gourmet chef who gleans for his restaurant, a homeless doctorate in biology who teaches literacy courses to immigrants for free, a couple of artists who use trash in their work, and the grandson of early cinema innovator Étienne-Jules Marey. Along the way, Varda discusses heart-shaped potatoes, big trucks on the highway, the waste of consumerism, and the ravages of time. This film was screened at the 2000 Cannes and Toronto Film Festivals.

FILM FESTIVAL REVIEW; A Reaper of the Castoff, Be It Material or Human

''The Gleaners and I'' takes its title, and some of its inspiration, from an 1867 painting by Jean-Francois Millet that shows three women in a wheat field, stooping to pick up sheaves and kernels left behind after the harvest. The image is well known; it appears in the Larousse Dictionary of the French Language alongside the definition of the verb ''glaner'' (to glean). The painting itself, which hangs in the Musee d'Orsay in Paris, shows up early in Agnes Varda's wonderful new documentary, thronged by camera-wielding tourists.

The painting -- or, more accurately, the activity it depicts -- sent Ms. Varda, a warm, intrepid woman in her early 70's and one of the bravest, most idiosyncratic of French filmmakers, on a tour of her own. From September 1999 until May of this year, she crisscrossed the French countryside with a hand-held digital video camera and a small production crew, in search of people who scavenge in potato fields, apple orchards and vineyards, as well as in urban markets and curbside trash depositories. Some are motivated by desperate need, others by disgust at the wastefulness all around them and others by an almost mystical desire to make works of art out of things -- castoff dolls, old refrigerators, windshield wipers -- that have been thrown away without a second thought.

Ms. Varda, their patient interlocutor, also sees herself as a gleaner in her own right. (The film's French title, ''Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse,'' makes this plain.) She plucks images and stories from the world around her, finding beauty and nourishment in lives and activities the world prefers to ignore. She is a constant, funny presence in the film, providing piquant voice-over narration and allowing herself visual and verbal digressions on the state of her aging hands, the water damage on her ceiling and her portable camera's dancing lens cap.

She is also an indefatigably curious, skeptical and sympathetic observer. ''The Gleaners and I'' is both a diary and a kind of extended essay on poverty, thrift and the curious place of scavenging in French history and culture. The patrons of a provincial bar explain the difference between gleaning and picking; a magistrate in black robes stands in a cabbage field and cites the section of the French penal code (Article R-26.10) and the royal edict of Nov. 2, 1554, that establish the right to glean. This bureaucratic side of the national temperament is also embodied by an apple farmer who explains the system he has developed for registering and licensing those who wish to gather his unharvested fruit.

For all its gentle humor -- there is a hilarious dispute about just how many oysters one is allowed to gather after a storm -- Ms. Varda's film uncovers a subterranean world of poverty and loneliness in the midst of plenty. An elderly peasant woman recalls the old days, when, as in Millet's painting, gleaning was a communal activity, festive and sociable even as it was backbreaking. Now, Ms. Varda notes, people scavenge alone, and they gather not only agricultural surplus but supermarket trash as well.

And yet ''The Gleaners and I'' is never depressing. Even at their most desperate -- a former truck driver, fired for drinking on the job, who lives in a shabby trailer; a group of disaffected young people who vandalize hulking trash bins -- Ms. Varda's gleaners retain a resilient, generous humanity that is clearly brought to the surface by her own tough, open spirit.

The film is studded with found metaphors and serendipitous insights, like the collection of heart-shaped potatoes Ms. Varda brings home from her travels. They're coarse, homely objects, misshapen and flecked with dirt, unmarketable in the view of the potato growers. But their poetic value is self-evident. ''I'm something of a leftover myself,'' Ms. Varda remarked to journalists covering the New York Film Festival, where ''The Gleaners and I'' will be shown tomorrow night. This was a charming bit of modesty. She's a treasure.

THE GLEANERS AND I

Directed by Agnes Varda; commentary (in French with English subtitles) by Ms. Varda; directors of photography, Stephane Krausz, Didier Rouget, Didier Doussin, Pascal Sautelet and Ms. Varda; edited by Ms. Varda and Laurent Pineau; music by Joanna Bruzdowicz; produced by Cine Tamaris; released by Zeitgeist Films. Running time: 82 minutes. This film is not rated. Shown with a 10-minute short, Eric Oriot's ''Later,'' tomorrow at 7 p.m. at Alice Tully Hall as part of the 38th New York Film Festival.

WITH: Bodan Litnanski, Agnes Varda and Francois Wertheimer.

In Agnes Varda's documentary The Gleaners & I (a more literal translation from the original French would be "The Gleaners & The Gleaner", or even "The Gleaneress") play, investigation, and contemplation are all intricately yet loosely wound together – each element distinct yet forming an unpretentiously ambitious whole, much like the found-object artworks Varda highlights throughout. Her subject, as you might have gathered (no pun intended), is gleaning: in all its forms. We are introduced to the classical gleaners, the peasant women who would follow the harvest by crouching and stooping through the fields, rummaging for leftovers once the more illustrious agricultural bounty was carried off. We see such gleaners in famous French paintings, and meet one or two who reminisce only – it seems that this more traditional form of gleaning has fallen by the wayside: mechanized reaping has become too precise and so few crops are left behind these days. This we learn in the first five minutes of the 90-minute film; what follows is an eager, inquisitive investigation of gleaning in all its latter-day manifestations…

We travel back and forth across France "capturing" passing trucks; shuffle through potato wastelands alongside single mothers and homeless alcoholics; observe running legal commentaries offered by robed justices standing incongruously in vineyards and in trash heaps. We see gleaners in vineyards, along the seashore, on city streets; meet various artists who incorporate abandoned junk into their own work; visit a children's museum which makes trash shiny and colorful. Finally we discover a post-graduate gleaner who picks through garbage to find food, his eccentricity giving way to erudite pedagogy when it's revealed that he teaches French to Senegalese immigrants, free of charge, of his own volition. Those are the gleaners – what of "I" (or as the original title puts it, the gleaner – singular)? She's Varda, of course, perpetually playing peekaboo with her own camera, narrating with a mixture of carefree bravado, pensive reflection, and endless fascination. Much, if not most, of what we see is filmed by her, so even when we aren't hearing or seeing her, she's present – the video filters her vision and consciousness, which together filter the outside world for us.

The lo-fi visuals are at once liberating and relatively nondescript – they do not carry the punch of celluloid, the automatic "magic", but they do convey a quiet, gentle charm, a looseness that is more observational and in some ways more sensitive than traditional filmmaking allows. This highlights the distinction between what is captured and how Varda captures it (the raw material of reality and the way she selects, composes, edits, comments upon, and interacts with what we see). This formal component provides a nice rhyme for the film's thematic material, in which utilitarian consumer goods are given aesthetic rebirth, waste is turned into food, and trash becomes personalized and beautiful. The aesthetic becomes practical, the practical becomes aesthetic, and the useless finds its uses – or rather has them found for it. Right away, the movie presents an awareness of beauty's ambiguity, opening not just with footage of gleaners at work, but gleaners glamorized, in the paintings of Millet and Breton. (Following a grim episode focusing on the dire poverty of some gleaners, there's a moment of reflection in Burgundy for Van der Weyden's "The Last Judgement", and briefly the film is haunted by the pitiable writhing of the damned.)

In presenting those works of art that commemorate gleaning, Varda seems aware that such paintings tend to romanticize what can be a very hard way of living – and yet to deny the beauty of these paintings would be absurd, and self-defeating. Varda's own filmmaking style, an engaging combination of doc and home movie, strikes an ongoing, fragile balance between respect for those she is filming and an almost naive sense of wonder; in both cases, curiosity serves her, and us, best. We draw our own conclusions without feeling that she has concealed her own point of view from us – or, at the same time, that her own point of view is necessarily any more fixed than our own. At times metatextual (but very, very playfully so), the movie – shot on a video camera at the turn-of-the-millennium – seems a synthesis of various documentary traditions, stretching all the way back to Etienne-Jules Marey, whose "chronophotography" was a forerunner of the cinema. (Marey's great grandson owns a vineyard which Varda visits, examining both his sympathetic treatment of gleaners and curation of a museum honoring his ancestor.)

Indeed, Varda has "gleaned" all the documentary techniques and approaches of the past hundred years: the personal diary, the man-on-the-street interview, the verite observation, the didactic montage, the found footage, the expert fact-finding interview – and all viewpoints are explored, political, personal, social, aesthetic alike. And what frames all of this borrowing, what gives it its own life, is Varda's use of the video camera – the way she filters all these devices through the humble yet infinitely resonant context of home moviemaking. (She even includes an accidentally-filmed "dance of the lens cap"; while some find such indulgence bizarre and laughable, many of us will find it charming, particularly those who recognize the complex framework within which such proudly amateurish moments are allowed to flourish.) To the extent the film has a "message" – generally it's more subtle and rich than that – it is an encouragement of this sort of personal gleaning; The Gleaners & I spurs us on to open our eyes and see the potential of society's refuse, the spiritual in the material, even as we are discouraged from ignoring the darker undertones of prettified consciousness. By the end of the film, encouraged by Varda's own highly individual, yet "open" perspective, that "I" in the title could be us as wellNo fruit left behind

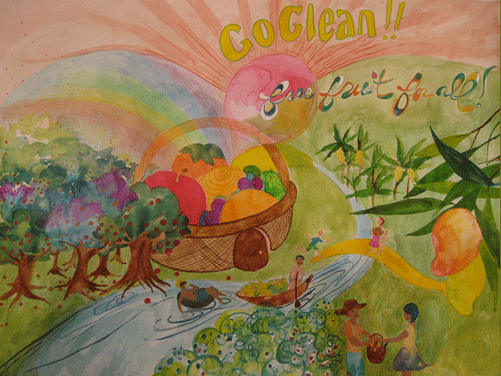

Two years ago, April Lee and Chetan Mangat were living in Honolulu and two experiences led them to create their new online produce exchange GoGlean.org. One night they saw Agnès Varda's film The Gleaners and I (a look at harvesting—as former agrarian duty and modern urban survival). It also happened to be mango season. They saw the irony of $2 Costa Rican mangoes being sold in a town where yardfuls of fruit were rotting.

"There are so many mangoes going to waste," said Lee by phone from Cambridge, where she is a student at Harvard's Graduate School of Education. "Then you go to markets and you expect to see local produce and for whatever reason you see imported fruits. It makes sense to create an online forum managed by the public. You supply them with the tool to connect them with each other."

The website is like a craigslist for fresh food. You open an account, and let people know what you have and where they can get it. Right now there are a couple of farmers on there, but a lot of the notices are for "found" fruit—people disclosing where the wild things are, such as "berries that look like blueberries" in Brooklyn's McCarren Park, or strawberry guavas on the loop trail in Keaiwa Heiau State Park. I don't know about you, but I don't want an hour hike to turn into a fruitless search. That's some lean gleaning. People also put out the word on more accessible pickins—April let people know about a treefull of "almost ripe pears spotted on the north/east side of the parking lot of Trader Joe's in Cambridge."

But as word spreads, site users may be finding themselves in situations more like the good ol' days portrayed in Vargas' documentary. "Chetan's been talking with farmers in New York, and they're keen on him going back to the original idea of connecting farmers with people," said Lee. "If people can take farmers' surplus it will be mutually beneficial for people and farmers, as farmers don't have to then get rid of the leftovers."

Lee and Mangat are the type of people who think nothing of cooking for hours for a houseful of people—some of whom they might not even know—and do it with genuine smiles. They offer GoGlean as a community service.

"We want people who want the food to get involved," says Lee, no matter where they are. If you happen to be going to Brazil soon, through GoGlean, you know you can get free surplus seasonal fruits and vegetables from Fazenda Armengue in Trancoso, Bahia. Lee knew Fazenda Armengue owner Rich Rossmassler when he ran Geneva, New York-based Red Jacket Orchards' greenmarket program in New York City.

Lee, originally from Honolulu, worked at the Honolulu Academy of Arts (where she was my colleague) as curator of special projects before moving to Los Angeles' Hammer Museum for a stint as a curatorial assistant. In Cambridge she is also studying at MIT's Media Laboratory. Mangat, who hails from India and makes his home in Brooklyn, founded Blank & Co., where his clients include the shop The Reed Space and Zing Magazine.

"We both are kind of involved in the possibilities of new media technology for community participation," says Lee. Along with GoGlean, Mangat has also developed the project The Labelmakers, an online effort to "allow every citizen to be actively involved in how we label our foods."

It's avocado season in Hawai'i right now. If you've got an overactive tree, go share your bounty online. 6 November

penis shaped potato

Earth's magnetic field:

Earth's magnetic field:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home