New Hints Seen That Red Wine May Slow Aging

New Hints Seen That Red Wine May Slow Aging

By NICHOLAS WADE -- Published: June 4, 2008

Red wine may be much more potent than was thought in extending human lifespan, researchers say in a new report that is likely to give impetus to the rapidly growing search for longevity drugs.

The study is based on dosing mice with resveratrol, an ingredient of some red wines. Some scientists are already taking resveratrol in capsule form, but others believe it is far too early to take the drug, especially using wine as its source, until there is better data on its safety and effectiveness.

The report is part of a new wave of interest in drugs that may enhance longevity. On Monday, Sirtris, a startup founded in 2004 to develop drugs with the same effects as resveratrol, completed its sale to GlaxoSmithKline for $720 million.

Sirtris is seeking to develop drugs that activate protein agents known in people as sirtuins.

“The upside is so huge that if we are right, the company that dominates the sirtuin space could dominate the pharmaceutical industry and change medicine,” Dr. David Sinclair of the Harvard Medical School, a co-founder of the company, said Tuesday.

Serious scientists have long derided the idea of life-extending elixirs, but the door has now been opened to drugs that exploit an ancient biological survival mechanism, that of switching the body’s resources from fertility to tissue maintenance. The improved tissue maintenance seems to extend life by cutting down on the degenerative diseases of aging.

The reflex can be prompted by a faminelike diet, known as caloric restriction, which extends the life of laboratory rodents by up to 30 percent but is far too hard for most people to keep to and in any case has not been proven to work in humans.

Research started nearly 20 years ago by Dr. Leonard Guarente of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology showed recently that the famine-induced switch to tissue preservation might be triggered by activating the body’s sirtuins. Dr. Sinclair, a former student of Dr. Guarente, then found in 2003 that sirtuins could be activated by some natural compounds, including resveratrol, previously known as just an ingredient of certain red wines.

Dr. Sinclair’s finding led in several directions. He and others have tested resveratrol’s effects in mice, mostly at doses far higher than the minuscule amounts in red wine. One of the more spectacular results was obtained last year by Dr. John Auwerx of the Institute of Genetics and Molecular and Cellular Biology in Illkirch, France. He showed that resveratrol could turn plain vanilla, couch-potato mice into champion athletes, making them run twice as far on a treadmill before collapsing.

The company Sirtris, meanwhile, has been testing resveratrol and other drugs that activate sirtuin. These drugs are small molecules, more stable than resveratrol, and can be given in smaller doses. In April, Sirtris reported that its formulation of resveratrol, called SRT501, reduced glucose levels in diabetic patients.

The company plans to start clinical trials of its resveratrol mimic soon. Sirtris’s value to GlaxoSmithKline is presumably that its sirtuin-activating drugs could be used to treat a spectrum of degenerative diseases, like cancer and Alzheimer’s, if the underlying theory is correct.

Separately from Sirtris’s investigations, a research team led by Tomas A. Prolla and Richard Weindruch, of the University of Wisconsin, reports in the journal PLoS One on Wednesday that resveratrol may be effective in mice and people in much lower doses than previously thought necessary. In earlier studies, like Dr. Auwerx’s of mice on treadmills, the animals were fed such large amounts of resveratrol that to gain equivalent dosages people would have to drink more than 100 bottles of red wine a day.

The Wisconsin scientists used a dose on mice equivalent to just 35 bottles a day. But red wine contains many other resveratrol-like compounds that may also be beneficial. Taking these into account, as well as mice’s higher metabolic rate, a mere four, five-ounce glasses of wine “starts getting close” to the amount of resveratrol they found effective, Dr. Weindruch said.

Resveratrol can also be obtained in the form of capsules marketed by several companies. Those made by one company, Longevinex, include extracts of red wine and of a Chinese plant called giant knotweed. The Wisconsin researchers conclude that resveratrol can mimic many of the effects of a caloric-restricted diet “at doses that can readily be achieved in humans.”

The effectiveness of the low doses was not tested directly, however, but with a DNA chip that measures changes in the activity of genes. The Wisconsin team first defined the pattern of gene activity established in mice on caloric restriction, and then showed that very low doses of resveratrol produced just the same pattern.

Dr. Auwerx, who used doses almost 100 times greater in his treadmill experiments, expressed reservations about the new result. “I would be really cautious, as we never saw significant effects with such low amounts,” he said Tuesday in an e-mail message.

Another researcher in the sirtuin field, Dr. Matthew Kaeberlein of the University of Washington in Seattle, said, “There’s no way of knowing from this data, or from the prior work, if something similar would happen in humans at either low or high doses.”

A critical link in establishing whether or not caloric restriction works the same wonders in people as it does in mice rests on the outcome of two monkey trials. Since rhesus monkeys live for up to 40 years, the trials have taken a long time to show results. Experts said that one of the two trials, being conducted by Dr. Weindruch, was at last showing clear evidence that calorically restricted monkeys were outliving the control animals.

But no such effect is apparent in the other trial, being conducted at the National Institutes of Health.

The Wisconsin report underlined another unresolved link in the theory, that of whether resveratrol actually works by activating sirtuins. The issue is clouded because resveratrol is a powerful drug that has many different effects in the cell. The Wisconsin researchers report that they saw no change in the mouse equivalent of sirtuin during caloric restriction, a finding that if true could undercut Sirtris’s strategy of looking for drugs that activate sirtuin.

Dr. Guarente, a scientific adviser to Sirtris, said the Wisconsin team only measured the amount of sirtuin present in mouse tissues, and not the more important factor of whether it had been activated.

Dr. Sinclair said the definitive answer would emerge from experiments, now under way, with mice whose sirtuin genes had been knocked out. “The question of how resveratrol is working is an ongoing debate and it will take more studies to get the answer,” he said.

Dr. Robert E. Hughes of the Buck Institute for Age Research said there could be no guarantee of success given that most new drug projects fail. But, he said, testing the therapeutic uses of drugs that mimic caloric restriction is a good idea, based on substantial evidence.

Sirtuin is a class of enzyme, specifically NAD-dependent histone deacetylases (class 3), found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. They have been known to affect cellular metabolism through selective gene expression in eukaryotes (plants and animals). The name comes from silent mating type information regulation two, the gene responsible for cellular regulation in yeast.

Sirtuins in lower eukaryotes

In yeast, roundworms, and fruitflies, sir2 is the name of the sirtuin-type enzyme. This research started in 1991 by Leonard Guarente of Harvard Medical School

Sirtuins as possible agents in retardation of the aging process

Sirtuins may be able to control age-related disorders in various organisms and in humans. These disorders include the aging process, obesity, metabolic syndrome, type II diabetes mellitus and Parkinson's disease. Normally, sirtuin activity is inhibited by nicotinamide, which binds to a specific receptor site. Drugs that interfere with this binding should increase sirtuin activity. Several studies show that resveratrol, found in red wine, can inhibit this interaction and is a putative agent for slowing down the aging process. However, the amount of resveratrol found naturally in red wine is too low to activate sirtuin, so potential therapeutic use would mandate purification and development of a therapeutic agent. Development of new agents that would specifically block the nicotinamide-binding site could provide an avenue to develop newer agents to treat degenerative diseases such as diabetes, atherosclerosis and gout.

Sirtuins types

Sirtuins are classed according to their sequence of amino acids. Prokaryotics are in class U. In yeast (a lower eukaryote), sirtuin was initially found and named sir2. In more complex mammals there are seven known enzymes which act as on cellular regulation as sir2 does in yeast. These genes are designated as belonging to different classes, depending on their amino acid sequence structure

Companies associated with the sirtuin enzymes

Companies associated with the sirtuin enzymes

Elixir Pharmaceuticals

Founded by Leonard Guarente, currently on the faculty at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with Cynthia Kenyon of the University of California at San Francisco, with the intentions of treating aging through drugs which affect metabolism.

Sirtris

Sirtris was co-founded by David Sinclair of the Harvard Medical School, and Dr. Christoph Westphal is the CEO

See also

* Sir2

* Resveratrol

* Biological immortality

* Caloric restriction

* Trichostatin A

* Histone deacetylases or HDACs

References

1. ^ EntrezGene 23410

2. ^ Patient Care, "Do antiaging approaches promote longevity?" By: David A. Sinclair, PhD, Evan W. Kligman, MD.

3. ^ "The quest for a way around aging", Nov. 8 2006, International Herald Tribune. By Nicholas Wade / The New York Times.

4. ^ Massachusetts Institute of Technology, News Office: "MIT researchers uncover new information about anti-aging gene."

5. ^ Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes; http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v450/n7170/abs/nature06261.html

6. ^ "New Hints Seen That Red Wine May Slow Aging" Jun. 4 2008, By Nicholas Wade, New York times

7. ^ Frye R (2000). "Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins". Biochem Biophys Res Commun 273 (2): 793–8. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3000. PMID 10873683.

Resveratrol is a phytoalexin produced naturally by several plants when under attack by pathogens such as bacteria or fungi. Resveratrol has also been produced by chemical synthesis, and is sold as a nutritional supplement derived primarily from Japanese knotweed. A number of beneficial health effects, such as anti-cancer, antiviral, neuroprotective, anti-aging, and anti-inflammatory effects, have been reported, but all of these studies are "in-vitro" (test tube) or in yeast, worms, fruit flies, fish, mice, and rats. Resveratrol is found in the skin of red grapes and is a constituent of red wine but, based on extrapolation from animal trials, apparently not in sufficient amounts to explain the "French paradox" that the incidence of coronary heart disease is relatively low in southern France despite high dietary intake of saturated fats.

The four stilbenes cis- and trans-resveratrol, and their glucosides cis- and trans-piceid are sometimes analyzed together as a group.

Chemical and physical properties

Resveratrol (3,5,4'-trihydroxystilbene) is a polyphenolic phytoalexin. It is a stilbenoid, a derivate of stilbene, and is produced in plants with the help of the enzyme stilbene synthase.

It exists as two geometric isomers: cis- (Z) and trans- (E), with the trans-isomer shown in the top image. The trans- form can undergo isomerisation to the cis- form when exposed to ultraviolet irradiation. Trans-resveratrol in the powder form was found to be stable under "accelerated stability" conditions of 75% humidity and 40 degrees C in the presence of air. Resveratrol content also stayed stable in the skins of grapes and pomace taken after fermentation and stored for a long period.

Plants and foods

Resveratrol was originally isolated by Takaoka from the roots of white hellebore in 1940, and later, in 1963, from the roots of Japanese knotweed. However, it attracted wider attention only in 1992, when its presence in wine was suggested as the explanation for cardioprotective effects of wine.

In grapes, resveratrol is found primarily in the skin, and -— in muscadine grapes —- also in the seeds. The amount found in grape skins also varies with the grape cultivar, its geographic origin, and exposure to fungal infection. The amount of fermentation time a wine spends in contact with grape skins is an important determinant of its resveratrol content.

The levels of resveratrol found in food varies greatly. Red wine contains between 0.2 and 5.8 mg/L, depending on the grape variety, while white wine has much less — the reason being that red wine is fermented with the skins, allowing the wine to absorb the resveratrol, whereas white wine is fermented after the skin has been removed. Wines produced from muscadine grapes, however, both red and white, may contain more than 40 mg/L

Supplementation

Resveratrol nutritional supplements, first sourced from ground dried grape skins and seeds (sometimes from residual byproducts of winemaking), are now primarily derived from the cheaper, more concentrated Japanese knotweed which contains up to 187 mg/kg in the dried root.

As a result of extensive news coverage, sales of supplements greatly increased in 2006, despite cautions that benefits to humans are unproven. There is also concern in the scientific community that many of the currently-available resveratrol supplements contain little or none of the active ingredient.

Physiological effects

Life extension

The groups of Howitz and Sinclair reported in 2003 in the journal Nature that resveratrol significantly extends the lifespan of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.Later studies conducted by Sinclair showed that resveratrol also prolongs the lifespan of the worm Caenorhabditis elegans and the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.In 2007 a different group of researchers was able to reproduce the Sinclair's results with C. elegans but a third group could not achieve consistent increases in lifespan of Drosophila or C. elegans.

In 2006, Italian scientists obtained the first positive result of resveratrol supplementation in a vertebrate. Using a short-lived fish, Nothobranchius furzeri, with a median life span of nine weeks, they found that a maximal dose of resveratrol increased the median lifespan by 56%. Compared with the control fish at nine weeks, that is by the end of the latter's life, the fish supplemented with resveratrol showed significantly higher general swimming activity and better learning to avoid an unpleasant stimulus. The authors noted a slight increase of mortality in young fish caused by resveratrol and hypothesized that it is its weak toxic action that stimulated the defense mechanisms and resulted in the life span extension. Later the same year, Sinclair reported that resveratrol counteracted the detrimental effects of a high-fat diet in mice. The high fat diet was compounded by adding hydrogenated coconut oil to the standard diet; it provided 60% of energy from fat, and the mice on it consumed about 30% more calories then the mice on standard diet. Both the mice fed the standard diet and the high-fat diet plus 22 mg/kg resveratrol had a 30% lower risk of death than the mice on the high-fat diet. Gene expression analysis indicated the addition of resveratrol opposed the alteration of 144 out of 155 gene pathways changed by the high-fat diet. Insulin and glucose levels in mice on the high-fat+resveratrol diet were closer to the mice on standard diet than to the mice on the high-fat diet. However, addition of resveratrol to the high-fat diet did not change the levels of free fatty acids and cholesterol, which were much higher than in the mice on standard diet.

Cancer prevention

In 1997 Jang reported that topical resveratrol applications prevented the skin cancer development in mice treated with a carcinogen. There have since been dozens of studies of the anti-cancer activity of resveratrol in animal models but no clinical trials in humans. The effectiveness of resveratrol in animal cancer models is limited by its poor bioavailability. The strongest evidence of anti-cancer action of resveratrol exists for the tumors it can come into direct contact with, such as skin and gastrointestinal tract tumors. For other cancers, the evidence is equivocal, even if massive dose of resveratrol are used.

Thus, topical application of resveratrol in mice, both before and after the UVB exposure, inhibited the skin damage and decreased skin cancer incidence. However, oral resveratrol was ineffective in treating mice inoculated with melanoma cells. Resveratrol (1 mg/kg orally) reduced the number and size of the esophageal tumors in rats treated with a carcinogen. In several studies, small doses (0.02-8 mg/kg) of resveratrol, given prophylactically, reduced or prevented the development of intestinal and colon tumors in rats given different carcinogens.

Resveratrol treatment appeared to prevent the development of mammary tumors in animal models; however, it had no effect on the growth of existing tumors. Paradoxically, treatment of pre-pubertal mice with high doses of resveratrol enhanced formation of tumors. Injected high doses, resveratrol slowed the growth of neuroblastomas. It had no effect on lung and pancreatic cancers, and leukemia.

Athletic performance

Athletic performance

Johan Auwerx (at the Institute of Genetics and Molecular and Cell Biology in Illkirch, France) and coauthors published an online article in the journal CELL in November 2006. Mice fed resveratrol for 15 weeks had better treadmill endurance than controls. The study supported Sinclair's hypothesis that the effects of resveratrol are indeed due to the activation of SIRT1.

Nicholas Wade's interview-article with Dr. Auwerx states that the dose was 400 mg/kg of body weight (much higher than the 22 mg/kg of the Sinclair study). For an 80 kg (176 lb) person, the 400 mg/kg of body weight amount used in Dr. Auwerx's mouse study would come to 32,000 mg/day. Compensating for the fact that humans have slower metabolic rates than mice would change the equivalent human dose to roughly 4571 mg/day. Again, there is no published evidence anywhere in the scientific literature of any clinical trial for efficacy in humans. There is limited human safety data (see above). It is premature to take resveratrol and expect any particular results. Long-term safety has not been evaluated in humans.

In a study of 123 Finnish adults, those born with certain increased variations of the SIRT1 gene had faster metabolisms, helping them to burn energy more efficiently—indicating that the same pathway shown in the lab mice works in humans.

Pharmacokinetics

The most efficient way of administering resveratrol in humans appears to be buccal delivery

Buccal mucosa is mucous membrane of the inside of the cheek. It is non-keratinised and is continuous with the mucosae of the soft palate, under surface of tongue and the floor of the mouth.

that is without swallowing, by direct absorption through the inside of the mouth. When 1 mg of resveratrol in 50 mL solution was retained in the mouth for 1 min before swallowing, 37 ng/ml of free resveratrol were measured in plasma 2 minutes later. This level of unchanged resveratrol in blood can only be achieved with 250 mg of resveratrol taken in a pill form.

About 70% of the resveratrol dose given orally as a pill is absorbed; nevertheless, oral bioavailability of resveratrol is low because it is rapidly metabolized in intestines and liver into conjugated forms: glucuronate and sulfonate. Only trace amounts (below 5 ng/mL) of unchanged resveratrol could be detected in the blood after 25 mg oral dose. In humans and rats, this results in less than 5% of the oral dose being observed as free resveratrol in blood plasma. The most abundant resveratrol metabolites in humans, rats, and mice are trans-resveratrol-3-O-glucuronide and trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate. Walle suggests sulfate conjugates are the primary source of activity, Wang et al suggests the glucuronides, and Boocock et al also emphasized the need for further study of the effects of the metabolites including the possibility of deconjugation to free resveratrol inside cells. Goldberd who studied the pharmacokinetics of resveratrol, catechin and quercetin in humans concluded that "it seems that the potential health benefits of these compounds based upon the in vitro activities of the unconjugated compounds are unrealistic and have been greatly exaggerated. Indeed, the profusion of papers describing such activities can legitimately be described as irrelevant and misleading. Henceforth, investigations of this nature should focus upon the potential health benefits of their glucuronide and sulfate conjugates."

The hypothesis that resveratrol from wine could have higher bioavailability than resveratrol from a pill, has been disproved by experimental data. For example, after five men took 600 mL of red wine with the resveratrol content of 3.2 mg/L (total dose about 2 mg) before breakfast, unchanged resveratrol was detected in the blood of only two of them, and only in trace amounts (below 2.5 ng/mL). Resveratrol levels appeared to be slightly higher if red wine (600 mL of red wine containing 0.6 mg/mL resveratrol; total dose about 0.5 mg) was taken with meal: trace amounts (1–6 ng/mL) were found in four out of ten subjects. In another study, the pharmacokinetics of resveratrol (25 mg) did not change whether it was taken with vegetable juice, white vine or white grape juice. The highest level of unchanged resveratrol in the serum (7-9 ng/mL) was achieved after 30 minutes, and it completely disappeared from blood after 4 hours. The authors of both studies concluded that the trace amounts of resveratrol reached in the blood are insufficient to explain the French paradox. They concluded that the beneficial effects of wine could be explained by the effects of alcohol or the whole complex of substances it contains

Adverse effects and unknowns

While the health benefits of resveratrol seem promising, one study has theorized that it may stimulate the growth of human breast cancer cells, possibly because of resveratrol's chemical structure, which is similar to a phytoestrogen. However, other studies have found that resveratrol actually fights breast cancer. Citing the evidence that resveratrol is estrogenic, some retailers of resveratrol advise that the compound may interfere with oral contraceptives and that women who are pregnant or intending to become pregnant should not use the product, while others advise that resveratrol should not be taken by children or young adults under 18, as no studies have shown how it affects their natural development. A small study found that a single dose of up to 5 g of trans-resveratrol caused no serious adverse effects in healthy volunteers

Mechanisms of action

The mechanisms of resveratrol's apparent effects on life extension are not fully understood, but they appear to mimic several of the biochemical effects of calorie restriction. A new report indicates that resveratrol activates SIRT1 and PGC-1? and improve functioning of the mitochondria. Other research calls into question the theory connecting resveratrol, SIRT1, and calorie restriction.]

An article in press as of January 2008 discusses resveratrol action in cells. It reports a 14-fold increase in the action of MnSOD. MnSOD reduces superoxide to H2O2, but H2O2 is not increased due to other cellular activity. Superoxide O2- is a byproduct of respiration in complex 1 and 3 of the electron transport chain. It is "not highly toxic, can extract an electron from biological membrane and other cell components, causing free radical chain reactions. Therefore is it essential for the cell to keep superoxide anions in check." MnSOD reduces superoxide and thereby confers resistance to mitochondrial dysfunction, permeability transition, and apoptotic death in various diseases. It has been implicated in lifespan extension, inhibits cancer (e.g. pancreatic cancer ), and provides resistance to reperfusion injury and irradiation damage . These effects have also been observed with resveratrol. Ellen et al propose MnSOD is increased by the pathway RESV --> SIRT1 / NAD+ --> FOXO3a --> MnSOD. Resveratrol has been shown to cause SIRT1 to cause migration of FOXO transcription factors to the nucleus which stimulates FOXO3a transcriptional activity and it has been shown to enhance the sirtuin-catalyzed deacetylation (activity) of FOXO3a. MnSOD is known to be a target of FOXO3a, and MnSOD expression is strongly induced in cells overexpressing FOXO3a .

Resveratrol interferes with all three stages of carcinogenesis - initiation, promotion and progression. Experiments in cell cultures of varied types and isolated subcellular systems in vitro imply many mechanisms in the pharmacological activity of resveratrol. These mechanisms include modulation of the transcription factor NF-kB, inhibition of the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP1A1 (although this may not be relevant to the CYP1A1-mediated bioactivation of the procarcinogen benzo(a)pyrene), alterations in androgenic actions and expression and activity of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes. In some lineages of cancer cell culture, resveratrol has been shown to induce apoptosis, which means it kills cells and may kill cancer cells. Resveratrol has been shown to induce Fas/Fas ligand mediated apoptosis, p53 and cyclins A, B1 and cyclin-dependent kinases cdk 1 and 2. Resveratrol also possesses antioxidant and anti-angiogenic properties.

Resveratrol was reported effective against neuronal cell dysfunction and cell death, and in theory could help against diseases such as Huntington's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Again, this has not yet been tested in humans for any disease.

Research at the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and Ohio State University indicates that resveratrol has direct inhibitory action on cardiac fibroblasts and may inhibit the progression of cardiac fibrosis.

According to Patrick Arnold it also significantly increases natural testosterone production from being both a selective estrogen receptor modulator and an aromatase inhibitor.

In December, 2007, work from Irfan Rahman's laboratory at the University of Rochester demonstrated that resveratrol increased intracellular glutathionelevels via Nrf2-dependent upregulation of gamma-glutamylcysteine ligase in lung epithelial cells, which protected them against cigarette smoke extract induced oxidative stress

Related compounds

Scientists are also studying three other synthetic compounds based on resveratrol which more effectively activate the same biological mechanism.

The compound called SRT 1720 seems to be 1000 times more effective than resveratrol, although it only increases SIRT1 activation by 6 times. No data has been publicly produced by Sirtris regarding this difference in SIRT1 efficiency for the new compound.

A study by Professor Roger Corder has identified a particular group of polyphenols, known as oligomeric procyanidins, which they believe offer the greatest degree of protection to human blood-vessel cells. These are found in greatest concentration in European red wines from certain areas, which correlates with longevity in those regions, though a causal effect is still unclear. This new data may impact the supplement market. Because they are present in red wine in more significant quantities, they could offer an alternate explanation of the French paradox

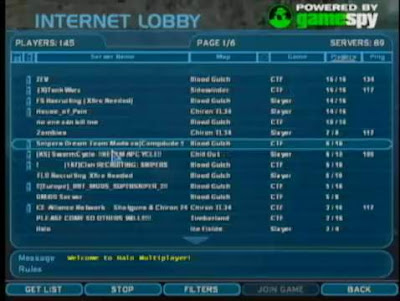

Sales Guy vs Web dude

Sales Guy vs Web dude

Connected to server. Loading map Blood Gulch

Connected to server. Loading map Blood Gulch

Utterpants - sex with vegetables

Utterpants - sex with vegetables

Don't use AOL -- that's for dial-up... you have broadband

Don't use AOL -- that's for dial-up... you have broadband

Take Screenshot - snapshot of the Screen - to go on Boing Boing

Take Screenshot - snapshot of the Screen - to go on Boing Boing

move them beyond the Desktop ... Customer happy..

move them beyond the Desktop ... Customer happy..

Earth's magnetic field:

Earth's magnetic field: